Gallery Artists, Roger Ballen had an insightful discussion with Michael Kirchoff…

“I am incredibly proud and honored to say that I had a lovely and informative discussion with the one and only Roger Ballen for this interview. As usual, I center the interview on an examination of the creative process, and with Roger being the consummate professional and arbiter of truth when it comes to his work, the art market, and the value of art in all its forms to the inquisitive public, we get straight to the heart of his ideas and passion.

Admittedly, I will say that I felt it was a shot in the dark to be granted this interview, but then I had the thought that trying now, while experiencing a worldwide lockdown during a pandemic was my best bet. You’ll hear more about it in the actual interview, but let me say that I was right. It doesn’t happen all the time, but in this instance, I played it smart. In fact, his creative endeavors while being locked down have brought about new opportunities for him, and I am eager to see where they go. Again, just a tease of what you’ll learn here.

I often think it presumptuous of me to think that I’m somehow qualified to pose questions to so many incredibly talented and creative people, but as usual, it is my curiosity that takes over and I just go into auto-pilot and move through it. I also think it’s good to not already know everything about anyone whom I speak to. Leaving myself open to ask the obvious or dare I say it, stupid question keeps the dialogue open for many to explore a new or different way of expressing an answer that they have not considered or answered often before. I suppose this is my own psychological observation about myself and isn’t it fitting that it might occur in the midst of an interview with the multi-talented and inspiring Roger Ballen.

If Roger has succeeded in making me think and explore my own thoughts, I know that he would appreciate this admission, for it is imagery like his that facilitates inner thought. Let’s just say, that’s why I’m here. Viewers of his work find that it is more than simply “looking at pictures” when up close and personal with a Ballen image, installation, or film. Something striking and profound can often be experienced when confronted with the dialogue one may have with themselves in the inspection of his works. It is exactly this that piqued my own curiosity in conducting this interview. Roger, of course, does not disappoint.” – Michael Kirchoff

Biography

One of the most influential and important photographic artists of the 21st century, Roger Ballen’s photographs span over forty years. His strange and extreme works confront the viewer and challenge them to come with him on a journey into their own minds as he explores the deeper recesses of his own.

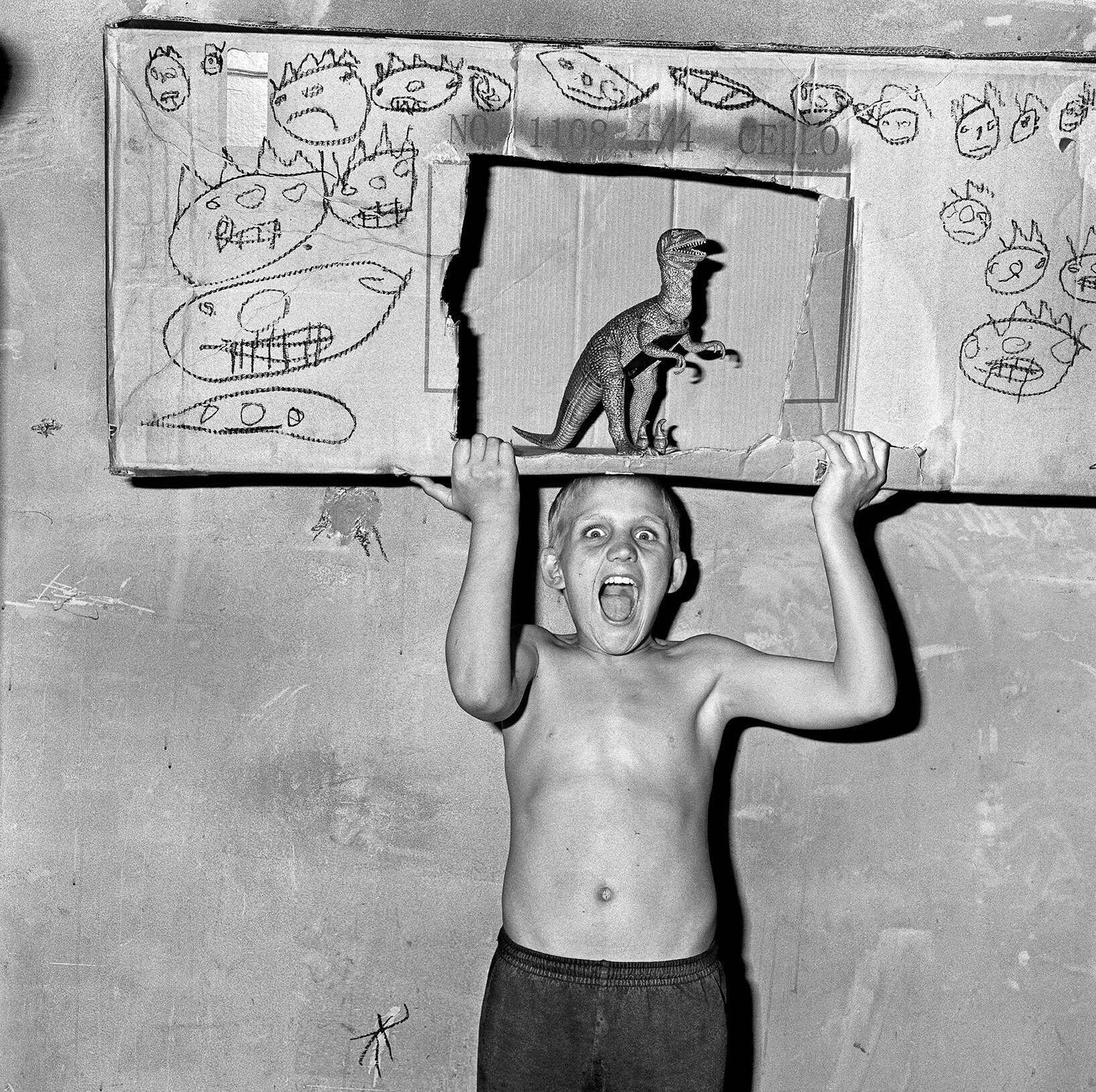

Roger Ballen was born in New York in 1950 but for over 30 years he has lived and worked in South Africa. His work as a geologist took him out into the countryside and led him to take up his camera and explore the hidden world of small South African towns. At first, he explored the empty streets in the glare of the midday sun but, once he had made the step of knocking on people’s doors, he discovered a world inside these houses which was to have a profound effect on his work. These interiors with their distinctive collections of objects and the occupants within these closed worlds took his unique vision on a path from social critique to the creation of metaphors for the inner mind. After 1994 he no longer looked to the countryside for his subject matter finding it closer to home in Johannesburg.

Over the past thirty-five years, his distinctive style of photography has evolved using a simple square format in stark and beautiful black and white. In the earlier works in the exhibition his connection to the tradition of documentary photography is clear but through the 1990s he developed a style he describes as ‘documentary fiction’. After 2000 the people he first discovered and documented living on the margins of South African society increasingly became a cast of actors working with Ballen in the series’ Outland (2000, revised in 2015) and Shadow Chamber (2005) collaborating to create powerful psychodramas.

The line between fantasy and reality in his subsequent series’ Boarding House (2009) and Asylum of the Birds (2014) became increasingly blurred and in these series, he employed drawings, painting, collage and sculptural techniques to create elaborate sets. There was an absence of people altogether, replaced by photographs of individuals now used as props, by doll or dummy parts or where people did appear it was as disembodied hands, feet and mouths poking disturbingly through walls and pieces of rag. The often improvised scenarios were now completed by the unpredictable behaviour of animals whose ambiguous behaviour became crucial to the overall meaning of the photographs. In this phase, Ballen invented a new hybrid aesthetic, but one still rooted firmly in black and white photography.

In his artistic practice, Ballen has increasingly been won over by the possibilities of integrating photography and drawing. He has expanded his repertoire and extended his visual language. By integrating drawing into his photographic and video works, the artist has not only made a lasting contribution to the field of art but equally has made a powerful commentary about the human condition and its creative potential.

His contribution has not been limited to stills photography and Ballen has been the creator of a number of acclaimed and exhibited short films that dovetail with his photographic series’. The collaborative film I Fink U Freeky, created for the cult band Die Antwoord in 2012, has garnered over 150-million hits on YouTube. He has taken his work into the realms of sculpture and installation, at Paris’ Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature (2017), Australia’s Sydney College of the Arts (2016), and at the Serlachius Museum in Finland (2015) is to name but a few. The spectacular installation at Les Rencontres d’Arles 2017, “House of the Ballenesque” was voted as one of the best exhibitions for 2017. In 2018 at the Wiesbaden Biennale, Germany, another installation “Roger Ballen’s Bazaar/Bizarre” was created in an abandoned shopping centre.

Ballen’s series, The Theatre of Apparitions (2016), is inspired by the sight of these hand-drawn carvings on blacked-out windows in an abandoned women’s prison.

Ballen started to experiment using different spray paints on glass and then ‘drawing on’ or removing the paint with a sharp object to let natural light through. The results have been likened prehistoric cave-paintings: the black, dimensionless spaces on the glass are canvases onto which Ballen has carved his thoughts and emotions. He also released a related animated film, Theatre of Apparitions, which has been nominated for various awards.

In September 2017 Thames & Hudson published a large volume of the collected photography with extended commentary by Ballen titled Ballenesque Roger Ballen: A Retrospective.

Halle Saint Pierre in Paris opened an exhibition September 6th, 2019 titled The World According to Roger Ballen. Thames & Hudson published the book in French and English to accompany the show. His work will take over the entire space for a full year closing in August 2020.

Interview

Michael Kirchoff: Thanks for joining me Roger, I’m thrilled to have this chance to discuss your creative process in the hopes that your words and ideas might help others to identify and hone their own. Can we start with a brief background about what lead you into the visual arts in the first place?

Roger Ballen: Yes, definitely. See, my mother worked at Magnum in the Sixties, and she got friendly with people like Cartier-Bresson, Bruce Davidson, and Elliott Erwitt. All the famous photographers at the time, as well as Kertész. She was passionate about these people, and they came to the house – they gave her pictures, books. So she got so much meaning and passion and enthusiasm about her work in photography. And these pictures were laying all over the house and on the walls, and I started to identify with them. In 1968, when I graduated from high school, my parents gave me a Nikon camera. I remember, when I went to Woodstock at age 19, I was capable of taking good pictures. And why was I capable? Probably, and most importantly, is I had years and years of osmosis in looking at these famous photographs and having a real deep interest in them. So this, I think, laid the groundwork for my interest in photography. I’m sure I never would’ve even thought about this in a million years without it because I wasn’t interested in art. I was interested in sports and girls and that sort of thing. But you know, immediately when I took that camera out, I was able to take good pictures, and immediately I felt some spark of inspiration – a purpose in what I was doing. I got hooked.

MK: What did your mother ultimately think about your career as a photographer?

RB: Well, unfortunately, in 1973, she died.

MK: Oh my, I’m sorry.

RB: You know, she got cancer, and I’d just graduated from college. So, unfortunately, she didn’t see what happened. My father was a lawyer, and he didn’t really have any interest in the arts. He was very methodical and factual. He wasn’t emotional. He wasn’t a person interested in aesthetics. It was really something from my mother’s interest that got passed on to me, I think. I think that was the main reason. And then it just fed on itself.

MK: Well, what an incredible start. This is really wonderful to hear about. Being inspired by amazing images back then, and those that still continue to inspire people today.

RB: This was a special period in the history of photography, when the individual image had a value to it, you know? There was something special about an image and people respected that. Not like under this current time, when you look at an image and second later something else pops on the screen to make you forget what you just saw.

MK: True, yeah. They’re flying by at breakneck speed, certainly.

RB: (laughing) And you can’t even touch it. See, that’s also a difference, you know, when you can touch something, pick it up versus looking at it on screen. It’s a multi-dimensional, multi-sensory experience rather than a mono-dimensional experience. So that’s also another reason.

MK: Yes, the tactile experience.

RB: Tactile. Yeah, definitely.

MK: I feel that so many have already discussed and examined your work as being dark or disturbing, with fewer people feeling the opposite. I’m in the latter category, loving the mystery and desire to ask the deeper questions that arise from your images. It seems that so much of your work is created to elicit these questions. Responses from others are always so fascinating to me, and I wonder about your feelings towards what you or others are getting out of your aesthetic. Is this a satisfying or frustrating experience for you?

RB: I’ve been doing photography for 52 years now, so it’s been a habit, a passion, a need, and a challenge. It’s all these things – it’s part of my life. It’s like I don’t ask questions about whether I should be doing or shouldn’t be doing it. This is just part of Roger Ballen’s life – it’s like brushing your teeth in the morning. It’s not a question for me, and I guess I wouldn’t do it if I didn’t get anything out of it. I think I’m very lucky and very fortunate because there are a lot of very intelligent people around. I’m lucky in the sense that I have tools, which can be a camera or a video camera or paintbrush, or whatever. I actually have the tools that allow me to find out things about myself, about my life, and I can use these tools to efficiently and artistically – poetically, get to places that I couldn’t get to in my mind without them. So I guess I’m fortunate in that point of view. So it’s more than satisfying. It’s almost religious.

Roar, 2002, from ‘Shadow Chamber’

Skew Mask, 2002, from ‘Shadow Chamber’

The Chamber of the Enigma, 2003, from ‘Shadow Chamber’

Twirling Wires, from ‘Shadow Chamber’

MK: Quite often we find ourselves looking at your work from only the photographic aspects, but truly this is merely one form of expression that you engage in with the creation of any project. Is it the photographic object or the content of the image that should mean the most to people? Does this matter, and should the drawings and paintings in your photographs carry equal weight in the final product?

RB: For me, I’m very a formulistic artist photographer. Everything in the picture is totally organic. Everything in the picture is there for a reason. Every single thing should integrate with everything else. And if you leave something out or pull something out that should have been there, then the picture doesn’t have the same impact. This is really a serious problem in photography and the history of photography, unlike painting. Photography has been about content. One of the reasons that most photographs don’t have much power, is that there’s nothing organic about them – the picture’s not working as a whole. And if you want to get to a deeper level, if you want to actually get a picture that has a possibility of getting somewhere, it has to have an organic nature to it. In painting and sculpture, I think people are a lot more aware of this concept, because they put things together piece by piece by piece, whereas a photograph is seen globally, right? If you’re a painter, you’d have to put all the little pieces together to get it right. And what does the picture mean? Does it have any impact on me or the viewer? Most pictures don’t mean anything. So ultimately, the goal is to produce powerful, meaningful pictures that stay in people’s brains and some way or another transform their consciousness. That’s the goal.

MK: Yes, certainly. Actually, that raises a question for me about how a photograph might start. When you speak about the organic qualities of an image, I wonder with a lot of your work in particular, how much of it is set up ahead of time? Then would you just let the people, the animals, and the objects perform their own type of theater while you capture the action, or is there a lot of direction from you as well?

RB: No, there’s not much. Everything is me, ultimately. So if a person’s moving, or birds are moving, you have to be able to see whether that’s linking other things in the picture – whether it be an object or whether it be a wall drawing. Ultimately, these are very complex photographs involving thousands of steps to get here. And I’m like a juggler who’s been doing this a long time. When you first start, if you’re not very good at it, you maybe can throw two balls in the air. But I’m dealing with many, many variables and trying to integrate these together so I can create a coherent photograph that actually means something. But at the end of the day, you can’t tell a bird what to do, and you can’t tell a rat what to do in a photograph.

MK: It feels to me as though the drawn elements in your photographs often represent the unreal world, while photography itself is more often thought to represent reality. What prompts you to combine these elements?

RB: You know, that’s an interesting question. In 1973, for about three or four months I did a lot of painting, and this was quite an important period for me, though I didn’t really finish what I wanted to do. When I started taking pictures in South Africa in the late eighties, a lot of the people had drawings on the walls and some of the children drew on the walls, and I started to integrate the drawings with some of my photographs. So this is, in a way, how the drawings came about.

I think some important questions in my work are, what is real? What is unreal? What is Roger? What’s that place? What’s my own mind? What’s a dream, what’s reality? What’s this, what’s that? So the pictures have a complex connotation to them. You could say that drawings are a two-dimensional object in the space, while a three-dimensional thing, like a rose that might be there, is more real than the drawing. But in the picture, the drawing has the same reality as the rose. And they’ve got to work together to create a greater whole that they are there for, not just being there in themselves. So the drawing should have the same weight as everything else in the picture. It is not any more real or unreal because it’s a drawing.

Five Hands, 2006, from ‘Asylum of the Birds’

Onlookers, 2010, from ‘Asylum of the Birds’

Ritual, 2011, from ‘Asylum of the Birds’

Take Off, 2012, from ‘Asylum of the Birds’

MK: How is a particular project conceived? Does the beginning of a photograph come solely from your subconscious and then built upon from the physical objects, paintings, and portraits of those you’ve met through your life, or are they more spontaneous and a reflection of your current state of mind while working?

RB: What I do is very hard to explain where it comes from. It’s hard enough to explain anything that you do, but something like this is impossible. It comes from my mind in some way or another. I don’t plan my pictures when I get there. Once I start to create them, it’s one thing after the next thing after the next thing, because there are so many unpredictabilities. There’s no point trying to figure out what I want to do because there are so many variables here. Number one, I don’t think about what I’m going to do, and number two, I never use words to define what my motive is. When I’ve told people over the years, if I can define a picture in words other than like ‘enigma’ or ‘mysterious’, then it’s probably a bad photograph.

MK: Does titling your photographs ever become problematic then?

RB: Well all of the pictures are titled. You can’t be in a situation where somebody says, “Oh, I love that puppy picture”, or “I love that little bird you put up with the drawing”. But a good title can add something to the picture. So, if I publish a work in a book, they’re always titled. I would never not leave one untitled. Some are better, some are worse. Some I would have liked to change, and some I’m happy with.

MK: Do the people appearing in your photographs have a say in how an image is represented? Do they provide feedback or desires on how to appear? How much of a collaboration is this, or do you remain steadfast in how you want them to engage the camera?

RB: I would call them Art Brut subjects. They’re not artists. They’re not interested in photographs. They’re not interested in art. They’re not interested in what I’m doing, but they like me and they liked being involved. It’s employment for them basically and makes them feel purposeful. So, you know, I’ve worked in some very bad places for like 30, 40 years, with chaos and violence and endless problems. But I don’t have problems with people because I’m always good to them. I treat them equally. I try to be positive – I respect them and they respect me. Most people wouldn’t last in these places beyond a day. I’m sure of this. They’re not really like actors in the true sense of the word. There are people who may try to do something funny, but they’re not that interested in the results at the end of the day.

MK: It’s just simply a job for them.

RB: It’s like a Samuel Beckett world – What are you doing today? I don’t know. What did you do yesterday? Nothing. What do you plan to do tomorrow? Nothing. So there’s no hope, no interest in going much further. You’re just living on a certain level and that’s it. This is an experience. It’s something to do that could maybe earn some money. It’s not to necessarily try to become an actor or a subject in Roger Ballen’s photographs. It’s none of that stuff. I always tell people that and in all my career, at least since I’ve been in South Africa, there’s never been one person from my photographs that’s ever even been in an art gallery or museum.

MK: Interesting. Do you ever go back and show them the photographs that you’ve made?

RB: Yeah. I show them pictures. In the old days, I always used to give them color pictures and they appreciated them.

MK: It’s a memory of a positive time in their life.

RB: It’s a valuable asset to a lot of people because they don’t have a lot of money and to have a photograph is special. But in the last 10 years now, there’s hardly any people in my pictures. It’s mostly birds, rats, animals, still lives, and mannequins. I would say 5% of the pictures actually have human beings in them. So my pictures have changed a lot – they’ve evolved.

MK: Do you feel that there have been any particular successes or failures you’ve experienced in the past that have helped you in the long run?

RB: I think that there was one particular period in my life that I think was interesting and had a big impact on my career. I published a book called Platteland, Images from Rural South Africa, in 1994, and it was photographed in the South African countryside. It concentrated on poor white people, mostly marginalized, living on the fringe. When this book was published, there was worldwide interest in it, and up to then, photography was really just an absolute hobby for me. I have a Ph.D. in Geology, and my job was as an exploration geologist. I had my own business trying to find minerals all over Africa. So photography wasn’t like a career. I didn’t want to do commercial photography. I don’t like it. And then I did this book, and it became like a worldwide phenomenon. But here in South Africa, I was extremely unpopular. The right-wing really didn’t like what I produced and the left-wing thought it was politically incorrect. In ’94, I’d tell people my only friend in this country was my dog. Susan Sontag had said it was one of the best books she’d seen in years, and I remember in South Africa, the biggest paper here said it was the worst book in years. So that’s where I was. But it created a lot of interest, and I said to myself, “I can’t believe it, there’s so many people interested in what I’m doing.” Ironically this experience gave me confidence. So beginning of ’95, I started working on the Outland book. Before that, the pictures in South Africa were in the countryside, but then they moved to around Johannesburg and I started photographing more disciplined work. I took my work a lot more seriously, and instead of going out to the countryside once a month or so, I started working three, four afternoons a week and started to take what I was doing seriously. So this was a very important event in my career.

Man Shaving on Verandah, Western Transval, 1986, from ‘Platteland’

Dresie and Casie, Twins, Western Transval, 1993, from ‘Platteland’

Sergeant F de Bruin, Department of Prisons Employee, Orange Free State, 1992, from ‘Platteland’

Wife and Daughter of Ostrich Farmer, Eastern Cape, 1990, from ‘Platteland’

MK: Up until fairly recently, your imagery remained in a black and white world, and you’ve now stepped into using color. What brought on this change, and are there others coming that we might see in the future?

RB: Well this, like a lot of things, just happened spontaneously after fifty years of doing black and white. When I was working on the video for the publication, Ballenesque, Roger Ballen: A Retrospective, Leica gave me a digital camera to create the video. And while I was shooting the video, I started to take some color pictures with the camera as well. I was so amazed that the photographs were good. I couldn’t believe it. Then I thought I’d make a few more, and some of the pictures in color were actually better than the black and white ones. I thought this is really interesting, I should try and do more of these. So for the last three years now, I’ve only worked in color, it’s a new challenge. It expanded my aesthetic. It’s been quite exciting.

MK: I would absolutely agree. What is it that you think occurred in you that changed your thoughts on liking color much more now?

RB: The images of the last three years could be thought of as so-called monochromatic colors – not bright colors. It is something almost between black and white in color and what I’m doing right now.

MK: More muted tones.

RB: More muted, yes. I’m happy I did this because you have to keep being challenged by what you do. You know, it’s always important to find things that give you a bit of a kick. This has been an interesting challenge in my career.

Disconnected, 2017, from ‘The World According to Roger Ballen’

Roger Ballen Drawing, ©Marguerite Rossouw, from ‘The World According to Roger Ballen’

Roger in the Family Room, 2014, ©Marguerite Rossouw, from ‘The World According to Roger Ballen’

Superman, 2018, from ‘The World According to Roger Ballen’

MK: I’m wondering if you have any formal relationship with psychology that has informed the work or methods used in their creation? Perhaps there is a fascination of your own in examining the viewer examining your work?

RB: My first degree is in psychology. I graduated University of California, Berkeley in ’72 with a psychology degree. I think I’ve had a psychological orientation for a long time. In the late sixties, early seventies, a lot of people were interested in psychology. Learning more about the self, the psyche. There was a general movement in the counterculture to learn about yourself in a deeper way, and I think that’s how it rubbed off on me. But you know again, people say, how does geology affect your work? How does psychology affect it? You can read 10 books on Freud, but when you go take the picture, you’ve still got the same problem. It’s a holistic understanding of the science of taking a picture and how to transform your feelings and your expression through a camera, which is based on a lifetime of experience.

MK: Was there a specific point in time where you felt that you had found your voice in photography and became satisfied with the direction of your work?

RB: I think during the Outland period – this was ’95 to 2000 – I think I found my voice. You could look at Platteland, and there were a lot of photographers from Diane Arbus to Sander, who took pictures of people on the fringe, people who had an element of marginalization, this sort of thing. So there was a documentary aspect to what I was doing up to about ’97. Beginning in about ’97, I started to create my own theater – a theater of Roger, a theater of Ballenesque – that went beyond just documenting what was there, and creating an aesthetic or a reality in the work that was particular to me in some way or another. Then I started to build on that. When Outland was published in 2000, I won a lot of awards and got a lot of shows. And again, this was an important point of my career when it got published, because I was, as I told you, starting to take things more seriously, but photography was still a bit of a hobby. And then this book really became a very famous book and I started to believe in myself a lot more, and put a lot more time and energy into creating photographs. I was able to grow my aesthetic because I spent the time and energy, and had some biological capability to do this. You can’t learn this. I think a lot of people go to these schools and spend hours and years to learn how to be an artist. But, there’s no simple way to become an artist and be able to express yourself in some creative or different way that has something that separates you from everything else, and actually has some deeper meaning. And I like to stress that idea, “meaning over time” because we see a lot of art that separates itself from other art, but it’s just gimmickry.

MK: What do you feel has proven to be a thorough culmination of your practice? Is there a specific project or body of work that you feel most proud of as being a premier example of your vision?

RB: I’m focused on what I’m doing now, and what I’m doing now is an integration of my 70 years on the planet and 52 years of doing these pictures. I can’t say, well Outland was better than my color pictures or my color pictures better than Outland. They all are part of my life, you know, in some way or another. Maybe in 50 years or 25 years, if I’m lucky enough, people will think about what I did and make value judgments on that. I can’t really say for myself which is better or worse. I’m not sure. I can do it with individual pictures. I can look at some of my pictures and say that this is like an iconic image, I can’t get much better than this picture.

MK: Clearly, it’s just that whatever is current in your life takes precedence.

RB: Yeah, it has to be, because otherwise what are you doing? You have to concentrate on what you’re doing – be focused, happy with what you’re doing, and inspired. Especially at my age, you’re really lucky. I’m lucky. I’m doing things I like doing and I’m inspired. I’m learning. I’m not sitting in some old age house somewhere.

Cat Catcher, 1998, from ‘Outland’

Head Below Wires, 1999, from ‘Outland’

Puppy Between Feet, 1999, from ‘Outland’

Tommy, Samson and a Mask, 2000, from ‘Outland’

MK: So what about the other side of the coin? Are there any times where you felt unfulfilled with something you’d done.

RB: Life is life. That’s all I can say. If you get good at something you like, you tend to do more of it. So the things that you love and feel something about do well, and the things you don’t, don’t do well. So for example, I don’t have an interest or any passion for commercial photography. I wouldn’t be good at it because I’m not interested in it, and I wouldn’t get any fulfillment out of it. It’s ideal if you can find something that you do for more than just money and really do it because you love it, and hopefully you make money at the same time. So for me, I was lucky, because I worked in geology, which I loved for 25 or 30 years, and it supported my photography. If I had just done photography, I would have been like the starving people I told you about it. So, you know, I’d have to quit and end up working at a bank or a large company and be frustrated.

MK: I suppose you wouldn’t ever get any kind of fulfillment if you didn’t have some sort of passion to begin with.

RB: Yeah, yeah. You usually don’t get any fulfillment unless you generally have some sort of passion. You know, this issue of fulfillment is also complicated because you can get fulfillment out of small things, like giving a dollar to a beggar, though you don’t necessarily have a passion for him. There are a lot of people in the art and photo business who’re basically in it to make money, and that’s their goal. It’s another profession to make money, and it’s not any different for them than being a lawyer or a doctor. It’s a professional career. So, you know, whether they have a passion for it or not, I can’t judge what other people do. We’re in a very difficult business. Maybe after this Coronavirus problem, there will be less people doing art and selling art. Maybe it’ll become a little more simple.

MK: Since we’ve been talking about careers and fulfillment, perhaps this is a good point to bring up the Roger Ballen Centre for Photographic Arts?

RB: Yes! So my building is almost finished in Johannesburg. Unfortunately, because we’ve had this lockdown, I was hoping to move in at the end of April, but now the building isn’t finished. Hopefully, by say, July, I can move in. The purpose of the building will be to mainly focus on work that has something indirectly, or directly, to do with Africa. It should have a psychological edge because I don’t want work that’s just showing the same old stuff. So it should, in a way, have something to do with my aesthetic, one way or another. It should be relevant to the audience here and it should be work that has an impact on people. This is the goal. I think most of the exhibitions will be group exhibitions. I think it should be arranged according to some sort of theme, rather than just showing individual artists. As a first step, I really need to move into the place and get to know it, and then start to try to find the best avenue to create a place that is a work of art itself. I also want to show videos and installations. So again, it has something to do with the things I do. It’s useful to have multimedia that has a parallel relationship with each other. You know, film can do certain things photography can’t do and vice versa. So if you use all these in an integrated way, then maybe you can create something more than just using one type of media, but you may just get the opposite effect if you don’t do a proper job.

MK: Wow, that sounds wonderful. Will you be the curator of the exhibitions as well?

RB: Hmm. I don’t know yet. I’ll probably hire visiting curators. I think that’s what I’m going to do. I mean, I have my own work, I travel a lot, and I don’t want to have everything piling on my head too. So I think I’d like to get individuals there that also have a vision and work with them to create something. You can have a curator, but I have to make sure that the standard that I’m trying to seek ends up being displayed, and it’s just not somebody’s ego on the wall that doesn’t actually represent the standard that I’m trying to achieve. I have to make sure that happens.

Amulet, 2011, from ‘The Theatre of Apparitions’

Embryonic, from ‘The Theatre of Apparitions’

Stare, from ‘The Theatre of Apparitions’

Waif, from ‘The Theatre of Apparitions’

MK: You began to move into the world of motion-based projects some time ago. How did this begin, and did you have any trepidations about taking your vision into this realm?

RB: This is a good question. Actually, believe it or not, my first film was done in Berkeley, in 1972.

MK: Oh, is that right? I had no idea.

RB: It’s called, Ill Wind. You can see some of the snaps in the Ballenesque book. So, the interesting thing is when you look at Outland and parts of Platteland, the type of character that was in this motion picture in ’72, is in these photographs 30 years later. Another good example is in 1973 when I did the painting for three or four months. Well, guess what I’ve done for the months of April and May during the lockdown here in South Africa? Every day, eight hours a day, painting for the first time on canvas since 1973. So the thing is, again, you shouldn’t do these things for the purpose of just doing them. You have to try to be on a certain level and feel a sense of passion. I think a lot of my films, they add to my aesthetic. They expand my aesthetic, and they expand my consciousness of the different media, so they all work towards a similar goal.

I’m also just finishing what I think is going to be a really interesting movie about a man who thinks he’s a rat. So this has been all shot, and I’m working on editing the film. It’s quite an inspiring piece. What I decided to do is, with each major project, is to make a film to go with it. This became manifested after I directed the I Fink U Freeky video with Die Antwoord. You know, the thing got like 150 million hits. So this gave me the motivation to make more videos, and I saw that making videos can bring your work to a lot more people than just producing still black and white pictures as long as it is on a certain level.

MK: So you didn’t go into the project with Die Antwoord knowing that it was going to be the success it was?

RB: I didn’t even know about YouTube, to tell you the truth.

MK: Well you certainly do now.

RB: (laughing) Yes, I do now. It would be interesting to see the difference in the amount of videos put on YouTube in 2012 versus whatever it is in 2020. To see a graph of how many videos are uploaded into YouTube from the beginning to the present. Just to see how that curve changes.

MK: Oh yeah. I believe I’ve seen some stats about that very thing. I’m sure it’s some staggering number that you would never imagine.

RB: Yeah. I see this all the time, and you’ve probably experienced this with what you’re doing. It’s harder and harder to get ideas across on the internet because there’s so much stuff. So when I first started to get interviews, like this one, I could see that there’s a lot of people looking at it, but I see that it’s really not easy to get people to read the stuff anymore. It’s so overloaded. Liberating in one way, but on the other hand, you’re just flooded. You just don’t know where to look after a while. You just feel like running away sometimes.

MK: True. That’s very true.

RB: I remember when I was at Berkeley and I had to write a paper. I went into the library, and Berkeley’s a big university – you went into the library, and you found like three or four articles and books to help write the paper. And now there’s 500,000 articles on the same thing.

MK: Right. Well, and honestly I thought about this too when I approached you about doing this interview. I thought, oh, he’s going to say, “No, I’ve already done so many interviews over the years. Why do I need to do another one?”

RB: Well, the timing was right, for two reasons. One is, I’ve been in isolation here for basically six weeks, so I was really looking forward to talking to somebody. And two, I liked what you were doing and this seems sincere. So when you sent me the sample questions, as I said, I was quite impressed.

MK: Well, thank you. Yeah, I guess I definitely caught you at the right time. That is certainly true. So what’s next then? Where will we find Roger Ballen in five years? Ten years? Any new projects in the works, or perhaps time off for good behavior?

RB: Yeah, yeah. Well, basically right now I’m doing, I think three or four major things. One is the color project – two, the Roger Ballen Centre for Photographic Arts – and three, the film on the man who thinks he’s a rat. I think that those are my projects that I’m mostly involved in right now. I guess for the next year or two, or three, that’s probably what I’ll be doing. Who knows, I don’t want to predict anything.

MK: So you definitely have a full plate. You’re not taking any time off, that’s for sure.

RB: No, no. The other thing is I enjoy what I’m doing. If I didn’t do this, I don’t know what I would do. This is what I’ve been doing all my life – it’s not work for me, it’s like a flow, you know? And some days are better, some worse, but you know, it’s as I said, I’m just fortunate that I have this – that I’m able to do this and feel this way about what I do. I’m lucky. Up until the last few months, I’ve been traveling, I travel a lot, especially living so far away. I think the hardest part of my career, in terms of being an artist, are the long trips, as South Africa is isolated from the center of the Art Business. If you’re going to show your work and develop a career in this business, you have to travel a lot. The shortest flight is 10 or 11 hours away from Johannesburg

I have a lot of exhibitions, and I enjoy some of them. Some are creative, for example, in Paris, The World According To Roger Ballen exhibition, to go with the book by Thames and Hudson, at the Halle Saint Pierre. It was a really great show. I took over the whole museum and it was supposed to be a whole year show, but unfortunately, like everything else, it got caught in this virus problem, so the exhibition closed in March and will re-open on June 10th.

MK: Well Roger, this was a lengthy conversation, I know, so I’ll let you get back to your painting.

RB: OK, take care, and I hope we see each other someday, sometime soon. I do thank you for your time and good work. Keep well.

MK: Thank you, you too. I sincerely appreciate every moment.

Article by Michael Kirchoff.

All photographs, ©Roger Ballen, unless otherwise noted.

View our online stockroom to see available works by Roger Ballen.